Step into the downwind passing lane.

Your quads burn, your lower back is tight and your hands are screaming at you to give them a break. The windward mark is in sight just ahead and with it a break from the hard work of sailing upwind. Hey, not so fast sailor.

If this is what’s running through your head at the end of a weather leg, I urge you to think again. Downwind sailing presents many opportunities to pass boats and to set yourself up to gain on the next upwind leg. The following article will give you some things to consider as you get ready to go downwind.

There are fewer shifts on the downwind leg:

When sailing upwind, we are sailing into or through the shifts. We look to position ourselves to take advantage of the next shift as it moves towards us. Upwind if we miss a shift there will often be many more opportunities to make up for that mistake.

Downwind, the wind, the apparent wind decreases. Now the shifts are going by us, but more slowly, as we sail with them. This places a bigger premium on the being the correct tack at all times. There are less chances to fix our mistakes. Downwind, there are effectively fewer shifts to take advantage of. This is why focusing mentally downwind leg is so important.

Clear air is king:

Just as upwind, it is important to be sailing in clear air as much as possible. The size of a boat’s wind shadow downwind is bigger than upwind due to the size of the spinnaker and the fact that

the boat is mostly being propelled by drag-induced forces.

A good rule of thumb to use is that disturbed air from another boat carries eight times the height of that boat’s mast away from before it reforms itself into the steady wind stream. Always keep this in mind. The effect is bigger in light winds and a bit smaller in stronger wind.

Eight times the height of the mast is a good rule of thumb to use for the distance disturbed air carries from a boat. On these Farr 40’s that’s about 480 feet! Photo: Bronny Daniels.

You have to know if you are in clear air or not:

To ensure that you are in clear air, always look at the masthead wind indicators of your competition. If they point at your sails, you are in their dirt. If their wind indicator in pointing in front of you your air is behind them, if it points behind you your wind is in front of them. On boats with multiple crew I suggest assigning one person to monitor this all the way downwind. This is a great job for one of your least experienced crews and a great way to teach someone the importance of sailing in clear air.

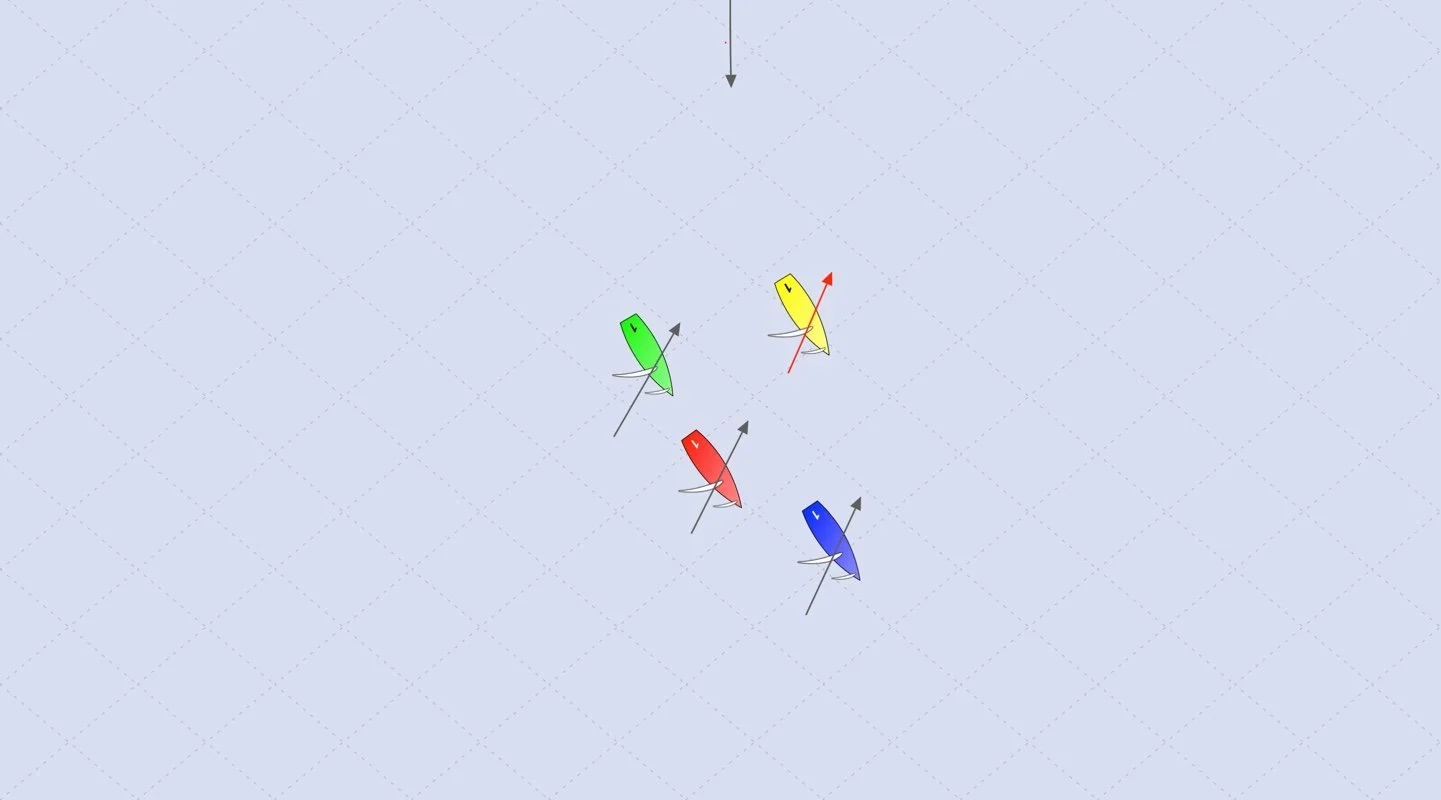

Watch the wind indicators of the boat above you for clues as to your wind. Red is in dirt, Blue has clear air ahead and Green clear air behind.

Your move when clear air is behind adjacent boat:

When your wind is behind adjacent boat’s that means you are somewhere between just even with them in the race or behind. In this situation, your goal is to position yourself to pass. You are looking to work your way to a spot so your breeze is either directly on their sails or better ahead of their sails.

If your clear air is behind the other boat your move is to stay at least parallel or better work down to create more of an athwartships gap between the two boats. The more lateral separation you can create the safer your position will be. Avoid sailing up into them and their wind shadow as much as possible.

Your move when clear air is ahead of adjacent boat:

When your clear air is ahead of another boat you are in front of them in the race. In this position, you are trying to protect and extend away from them so you can start working on the boat’s ahead of you.

You’ll want to work down when possible but because you don’t want them to advance forward enough to affect your wind you will often come up to “protect” your breeze. The best move is to work forward and down keeping your air clear ahead but gaining lateral separation. Then when both boats gybe you’ll be in a strong position ahead and to leeward.

Whether your wind is ahead or behind the other boat to keep your clear air you need to know the angle that the boats closest to you are sailing all the time. This is not the helmsman’s job. One of your team needs to be monitoring the angles of the other boats and talking about that pretty much constantly. This can be the same person who is monitoring the wind of the other boats.

Boatspeed is king:

Having good boatspeed downwind is just as important as it is upwind but I have found that good boatspeed downwind is much more about technique rather than tuning and trimming which can be key upwind. The overall golden rule is, “down in the puff and up in the lulls”. Use the increased pressure of a puff to work your way downwind and then come back up to a higher angle when the wind dissipates. Ideally your boat speed should stay relatively constant whether in a lull or puff.

The real skill is knowing how low to go in a puff and how high in a lull. On the top boats, the spinnaker trimmer is really steering the boat and directing the helm to come up or down as the pressure increases or drops. The trimmer must have a running dialogue with the helmsman on what angle he or she wants the boat at all times. He or she will have the best idea what angle the boat should be to the apparent wind and also will like be the first to feel a lifting or heading puff. If you are the helmsman you must work to encourage your trimmer to communicate as much as possible.

Also, it’s important on crewed boats is to have a dedicated person looking aft for pressure all the time and keeping the boat in ideally more pressure that the competition. This can take some skill and time to develop but is huge in terms of overall performance. You are looking to position the boat so that it will intersect areas of increased pressure as much as possible downwind. Good polarized sunglasses and an elevated position on the boat will help.

Making it happen

With some basics covered above, how in practice do we actually pass boats? Following are steps to follow and execute.

Get on the long tack as quickly as reasonably possible

Before the start make sure to note (write down) the heading from the start line (or ideally the downwind mark or gate) and the weather mark. From there determine the reciprocal course from the weather mark back to the leeward mark and write that down (add or subtract 180).

As you are approaching the windward mark it’s important to start thinking well ahead what gybe will be favored right as you start the downwind leg. For example, if you are approaching the mark on a starboard tack header it is likely that the long gybe will be on starboard. If however you are approaching in a lift it is pretty likely that the long gybe will be on port and you’ll want to gybe soon after the mark.

By having the heading to the downwind mark clear in your head and by knowing the gybing angles of your boat you should quickly be able to check if you are on the closest gybe to the leeward mark right away. Obviously, there are extenuating factors like the bad air from other boats and spots of pressure to go after that will change exactly when you want to get on the long gybe.

Continue to monitor your heading all the way down the run and work to stay on the headed gybe as much as possible while staying in clear air and in more pressure (easier said than done).

Especially if you are towards the front of the fleet as you round the windward mark you’ll need to keep in mind the bad air or the boats approaching the mark behind you. Sometimes the better move is to hold off on gybing just to avoid the dirty air created by the train of boats on the starboard tack layline. As always, there is a tradeoff. If one gybe is hugely favored it might pay to suffer through the bad air of the upwind boats to be one of the first boats on the correct gybe.

Position for the pass:

As stated before good speed is key. Put it to work for you by positioning for the pass. As you start to gain on a boat ahead of you whether through better speed or pressure work low of their line. The more distance to leeward the better. The reason is when both boats gybe the lower you are the closer you will be to being on the other boat’s wind or even have your bad air end up of in front of them. What you really want is enough separation so that when both boats gybe the new leeward boat is not overlapped to leeward. This is the ideal scenario for you.

Blue does a nice job of working low of yellow and passes when they gybe.

Protecting the pass:

Being the boat being overtaken can be frustrating but it is possible to keep boats close to from passing by working down whenever they do to always minimize the athwartships gap between the two boats. Your goal is to ensure that when both boats gybe your air remains in front to your competitor. If they are coming up fast with pressure you do not have, it’s often best to gybe early just to keep your air clear and options open. Again, it is important at all times to have someone looking behind and talking about the relative angle of the boat behind so you can match it and keep the boat going fast at all times.

Yellow matches blue’s angle as they come down and stay ahead when they gybe.

Keep it in the middle:

In order to pass boats that are in front of you you’ll need some runway to work with. The closer you get to the lay lines for the leeward mark downwind the fewer opportunities you have to work your opponent. Once you are on the lay line any opportunity to pass will be gone. At that point, you’re sailing straight to the mark. So be careful to keep shifting the action back towards the middle of the course to keep your passing options open.

Summing Up:

There are many other things to consider but these are some of the fundamentals to focus on:

· Realize there are fewer shifts downwind. They are important.

· Stay in clear at all times and know if the bad air from adjacent boats is in front, behind or directly on you.

· Boat speed is king. Focus on it…

· Have a dedicated crew member watch behind and call pressure and whether your air is clear or not. This should not be the helm or spinnaker trimmer.

· Get on the long gybe as quickly as reasonably possible…

· Position for the pass. Keep it low and fast.

· To prevent the pass work down to match the angle of the boat on your leeward quarter.

· If your gut says to gybe it’s probably right. Go for it. If you have good crew work and boat handling the penalty if you are wrong is pretty small.

· Keep your chances of passing alive by keeping it in the middle of the course unless you are leading or close to it.